The EU must drop its target for agrofuels which is putting food security at risk in many regions in Southeast Asia.

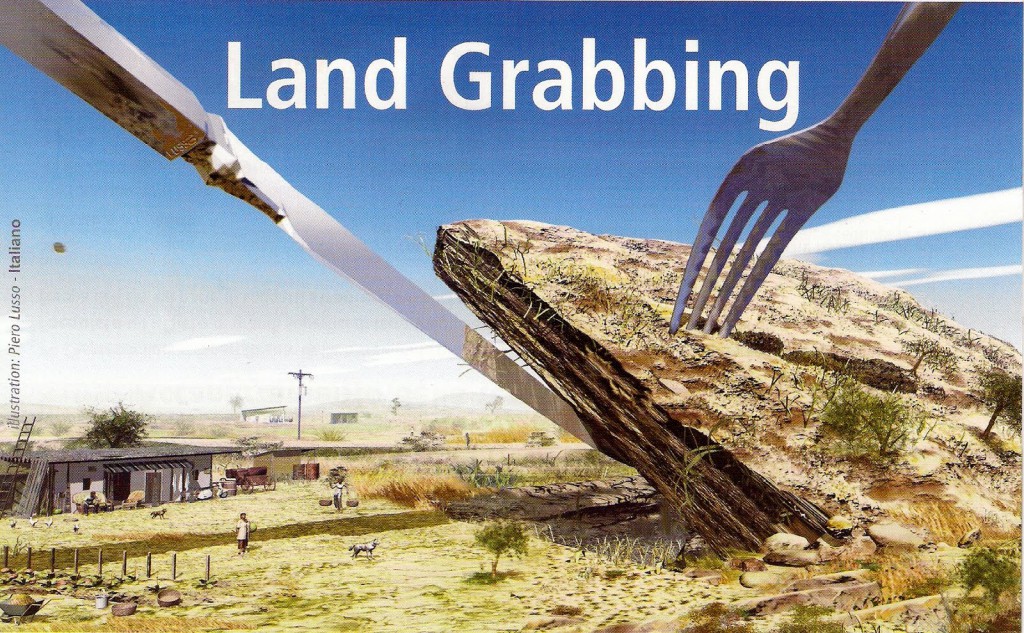

Land Grabbing is an emerging phenomenon resulting from “crop boom” in Southeast Asia. Small scale landholders and farmers, rural workers, and indigenous people are increasingly losing control over their land. There is a plethora of actors ranging from giant corporations, governments, international organisations, and regional players that are involved in this phenomenon. This article however focuses on the role of European Union in land grabbing in the Southeast Asian region.

The 20 percent mandatory target for renewable energy adopted by the European Parliament in 2008 had set the ball rolling for investment in agrofuels like oil palms across Southeast Asia: “Much of the oil palm expansion in Southeast Asia for European markets is driven by Malaysian and Indonesian capital, for example in the Philippines”. This OECD report reveals that financial companies are increasingly involved in global agricultural investment. Europe continues to expand its trade activities concerning agricultural food complex in Southeast Asia.

A stream of policies that directly or indirectly accelerate the process of land grab in the Global South is primarily based on the premise that the land can be turned into productive commodities that further pave way for profit making. Some European funds (i.e. pension funds such as the Swedish AP2, the Dutch APG and PGGM) have made significant deals concerning land. According to the report by OECD in 2010, financial actors in Europe make up for 44 percent of investment in land across the globe. Most of these land deals are rarely directed towards any productive investment and are bought only to sell it later at high prices. These land deals also overlook the economic, social and ecological costs that often disrupt the activities of local landholders and farmers.

The “Everything but Arms” trade policy followed by the EU gives the least developed countries the provision to import products to the EU without any duties and restrictions. This policy has accelerated sugar production in Cambodia which in turn has caused an increase in land grabbing. Lu Yong Phat, a Cambodian senator and businessman has bypassed the national law that limits the size of land acquisition to 10000 hectares and has instead acquired 60000 hectares land to produce sugarcane. The assistant of Lu Yong Phat has pointed out that the EBA to some extent is responsible for accelerating the process of land grabbing in the region, however EU has completely overlooked cases of inequality and human rights abuses spurred by its own policies.

Not only has the EU been oblivious to these concerns but has actively adopted the “win-win” formula and “code of conduct” approach pursued by international organisations like the World Bank whose policies promote land grabbing instead of preventing it. The latest policy on EU land grabbing hardly addresses any pertinent questions regarding “reserved agricultural lands” in the Global South which are considered to be solutions to the current food and energy crisis. These sets of policies twist and thwart the local realities and relations to elicit maximum profits. Moreover, industrial mono-cropping of oil palm and eucalyptus is widely practiced in South East Asia to restore the quality of degraded lands under the name of “Sustainable reforestation”. The redistributive nature of policies is almost nonexistent in many member states, and the “focus on land administration and technical approaches” is virtually blind to the existing political contours in the region. Since these policies disregard the local context, the voluntary nature of land agreements could be contested. The socio-economic and political realities in Southeast Asia are rarely equal and under such circumstances, the principle of free, prior and informed consent is rarely observed.

To meet the pattern of European food consumption, the land in the Global South is being heavily compromised thus widening the gulf of disparity. If Europe wants to push forward the sustainable development model, it must respect international law and dig deeper to address the human rights abuses that are direct consequences of its land deals. To achieve the same, the EU must activate its “Land Policy Guidelines for Support to Land Policy Design and Land Policy Reform Process in Developing Countries” which have certain progressive elements that can offer protection to the rights of small farmers and landholders. It must drop its target for agrofuels which is putting food security at risk in many regions in Southeast Asia. These steps would throw some light on the ongoing mismanagement in the context of land deals.

1 comment

1 Comment

EU’s Role in Land Grabbing in South East Asia – pratibhasinghweb

08/08/2016, 3:16 pm[…] Original Source: Politheor […]

REPLY