When walking the streets of Complexo da Maré in Rio, pluralism is engraved in various, albeit paradoxical, ways. Based on live field experiences, this op-ed tackles the social, political and religious twists and turns pluralism takes when entering one of Rio’s most contested spaces.

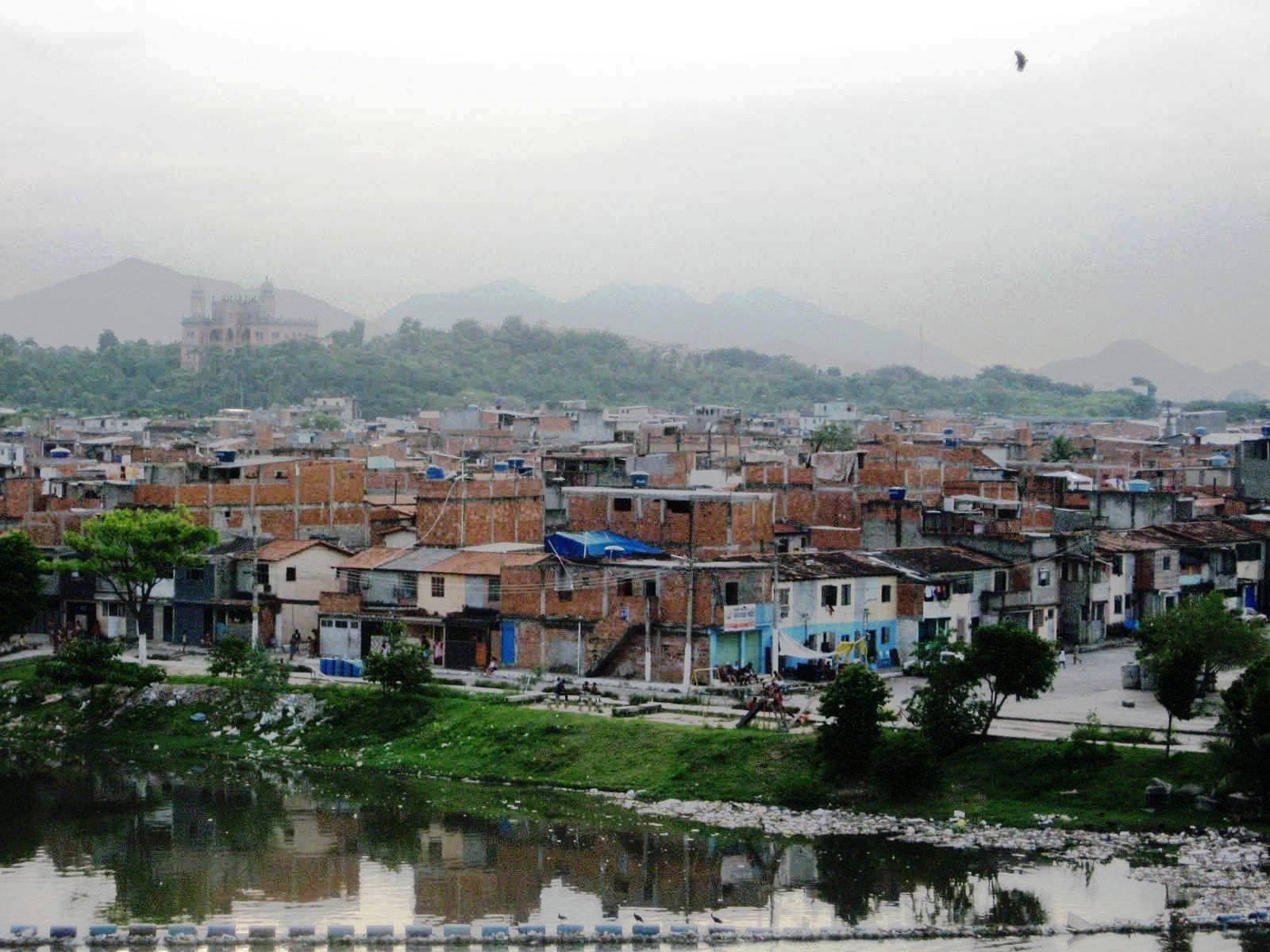

Locked in between the arms of Avenida Brasil, Linha Vermelha and Linha Amarela, Complexo da Maré (map), a conglomeration of 16 favelas in the city of Rio de Janeiro, has resisted attempts of police pacification so far. Back in 2014 Maré hit the international news when it was occupied by 1400 police and marines during the World cup.

When arriving to and walking in Maré, this precarious space shows a multitude of competing violent actors inscribed into vast geography. If Maré was to be a city it would be the 11th largest city in the state of Rio counting quasi 130000 inhabitants. Outside, along Avenida Brasil, the civil police of Maré stand guard. They do not enter. One could argue that they patrol here merely to show a sense of state presence as tourists travel from the international airport to the city center, leaving the favela at bay on its left hand side. Inside however, the distinct and interconnected territories are governed by competing drug factions, most notably Terceiro Comando Puro & Comando Vermelho. Two of its more remote communities are governed by Milicias: police-connected rogue protection groups opposing drug trafficking. These groups have over time consolidated, often violently, political and economic power in those communities by taxing its residents. Lastly, in some parts of the Complexo, the military police or even BOPE enter on a monthly basis reminding its residents of the state’s repressive force.

There is however another actor inscribing itself in Maré, one that confirms the argument that these spaces are neither a political vacuum, nor merely a marginal antinomy of state power, but rather the alteration of it. The evangelical church rose drastically in Brazil over the past two decades. Whereas parts of Europe turned secular, in Brazil the slow decline of Catholic power has been absorbed by Evangelicalism and most specifically its (neo)Pentecostal part. In fact, research indicates that a new Pentecostal church was established every day in Rio, gaining its strongest foothold in favelas through practices of tithing and exorcism and narratives of cure and prosperity.

When walking the streets of Maré, inscriptions of the gospel go hand in hand with drug faction symbols. During late night baile funke parties local chefs refer to biblical passages in the speakers; at the wake of day young traffickers read the bible as they prepare for their daily business at their boca de fumo. On a social or individual level, conversion to Pentecostalism offers a sense of protection, but it also counts as a performance of sobriety and reminds traffickers of the prospect to leave the business. During mass, the direct accumulation of wealth is praised together with an abstract, bipolar worldview in which the absolute evil needs to be destroyed. These elements resonate with the direct living experiences of youngsters in the world of trafficking.

The rise of Evangelicalism as a monolithic political power (most notably the conservative bancada evangelica) creates contingent effects on the ground with, for example, traffickers converting to it and leaving the business or even harmonizing evangelical ideology with their illicit businesses. On a larger scale, Evangelicalism establishes a political, conservative force in the favela. On the one hand it offers residents sandwiched between violent actors a sense of meaning and hope: you can preach the evangelicalism you want based on your personal desires and needs. On the other hand, its conservative character reduces the chance of a real social, progressive movement to reappear in the community.

The fall of the Berlin Wall lauded a politics of pluralism, multiculturalism and tolerance. It was the logical turn for many countries in the West after having witnessed the atrocities dictatorial regimes committed. On an individual level this coexists with the principle of expressive individualism and autonomy: the state should provide me with enough freedom and recognize me in turn as an individual.

In Latin-America, as Goldstein and Arias argue, the transition to democracy and the fear of a repressive government in effect generated and coexist with a pluralization of violence. In Brazil for example, together with the rejection of the dictatorial regime, the opening of Brazil as an international market and the rise of the Andean cocaine transport in the 80’s, a multitude of interconnected state and non-state violent actors started to govern the majority of the favelas until now. In Maré, Evangelicalism seamlessly intersects this multitude as a political and social phenomenon. Its business-like conservative narrative of individual prosperity offers a religious answer to the pluralism and the expressive individualism that guides our current worldview.

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked with *