The global financial and economic crisis has exposed a chasm between the theory and the practice of policy. Not only did the models underpinning policy choices not help anticipate the crisis, but now arguably they cannot even help fight it. Concerns are rising in the policymaking field that something structural – that models cannot capture – has changed. The stagnation afflicting the global economy could hence be a new normal, from which we can escape only by thinking out of the box of deceptively comfortable models.

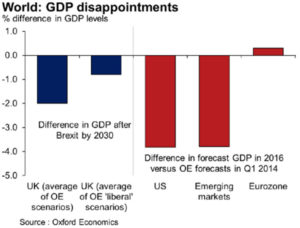

Most recently, the Brexit vote shed doubt over political and financial stability in the UK and the EU, sparking a jolt in volatility and leading to a downward revision of growth forecasts.

While Brexit should not be underestimated, I agree with Oxford Economics’ argument that the size of the initial global market sell-off cannot be entirely attributed to the impact of a weaker UK, or the pricing in of negative scenarios in the Eurozone. It more generally reflects investors’ perception of a constrained macroeconomic policy space and subsequent little confidence in the ability of existing policies to spur growth and avoid a next collapse.

Such stance is hardly unjustified. When the crisis erupted in 2007-2008, the instinct was to characterize the shock as temporary and reversible, a V-shaped disruption. There would be a sharp downturn, mainly resulting from the need to rebuild balance sheets and reduce public sector deficits and debt. Still, sooner or later recovery would pick up.

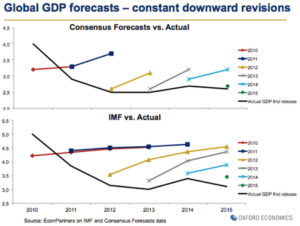

However, roughly a decade later, the economy has not bounced back. On the contrary, despite overall favorable background conditions – drop in oil and commodity prices, expansionary monetary policy and a relative ease in austerity stances – recovery remains muted almost everywhere, with advanced economies losing growth momentum and emerging market economies growing below potential.

Hence, policymakers are uncomfortably aware that their benchmark macroeconomic paradigms might fail them, just like they did before the crisis.

Is this a new normal?

Some elements would still lead to assume it is merely another turn of the business cycle. First, pronounced risks play a role: heightened geopolitical tensions and a return of financial turmoil impair confidence and demand in a self-reinforcing feedback loop.

Second, economic management might have been poor. There has been so far an overreliance on monetary policy and not always complementary action, in the form of structural reforms and debt reduction, was taken.

Also, perhaps expectations were too high. The crisis was a major blow to confidence. It hit consumers, businesses and financial actors too hard for things to quickly go back to pre-crisis status at the first sign of recovery.

Nevertheless, the idea is gaining ground that the pre-crisis world might not return. Other, more structural or longer-term dimensions might be operating in addition to cyclical drivers and imply that the world economy may have to adjust to a ‘new normal’ of fragile and low growth.

After all, traditional growth drivers – e.g. productivity and trade – lost steam and there are unfavorable fundamentals, such as high debt levels, low investment and an ageing population.

Growth forecasts seem to support this view. The significance of the forecast misses illustrated below (Courtesy of Emilio Rossi, Senior Advisor at Oxford Economics) goes beyond cyclical factors and the natural imprecision of models. Something structural might have changed and existing models cannot take it into account.

Against this background, policymakers must act cautiously. Not by chance Janet Yellen recently stated: “the economic outlook is uncertain, so monetary policy is by no means on a preset course”.

Against this background, policymakers must act cautiously. Not by chance Janet Yellen recently stated: “the economic outlook is uncertain, so monetary policy is by no means on a preset course”.

The question is, can we move away from this situation of stall? It seems far too hard. In a low growth environment, too ambitious targets might be chosen, potentially creating disequilibria and bubbles. In the case of a new crisis, policymakers would suffer from a shortage of instruments.

Monetary policy has been stretched to its limits with quantitative easing and zero interest rates, yet investment remains subdued and recovery struggles to gain momentum.

Fiscal policy is constrained by the need to reign in a huge debt burden.

Besides, in a context of continued political dysfunction and popular distress, a frustrating and mediocre new normal might be preferred to a new recession triggered by experimental policy choices.

Nevertheless, we can aim for a better “normal”. Something can be done. For one, the lack of fiscal space partly stems from financial market scrutiny, in the form of increased spreads and negative ratings. I am not sure this power of financial markets cannot be in part limited, for instance by re-defining the necessary, yet hardly fully reliable, role of credit rating agencies.

Also, pro-growth structural reforms – e.g. infrastructure investment – and investment in technology to unleash productive capacity might lead to faster and more inclusive growth.

Last but not least, global coordination could be enhanced for a systematic – hence effective – policy approach, showing that in a globalized and interconnected world the protection of national flag is just a delusion.

It is frustratingly unpredictable whether we will overcome the new normal of low growth and high uncertainty. Sure is that, for something to be done, we need to think out of the box of conventional, deceptively comfortable models. In particular, policymakers should be trained to think about the worst that could happen, even following their interventions. They cannot afford to think in terms of stability, but rather instability. This way, potentially new solutions to a new normal might be found.

1 comment

1 Comment

Brave New Euro | Politheor

11/11/2016, 4:40 pm[…] In the golden years everyone, but Germany, profited from the new currency. The Mediterranean countries especially benefited from the huge drop in interest on government bonds, which enabled them to spend more money. Many countries built up debt despite mechanisms in place to prevent that. At one point the music had to end. In 2008, the American housing bubble catalysed a global crisis, which then turned into a Euro-crisis. It made us wonder whether stagnation is the new normal. […]

REPLY