Stepping onto the battlefield that rages over the issue of net neutrality, even as an observer, is enough to make your head spin. There is a vast amount of often contradictory information to process, with each faction that provides it chanting vigorously in defense of their own viewpoint. Soon you realize that each outcry sounds roughly the same, some version of “if our plans are not enacted, the beautiful internet you have come to love will be controlled and damaged by the wrong people, and end up just a shadow of its current self”.

This article will not explain net neutrality (the Wikipedia article is one of the top 1% most contested, and therefore one of the best), nor will it attempt to find the truth among the competing factions. Rather it will take a step back and look at some often missed elements of the bigger picture. A follow-up article will continue further into the policy aspects of the issue by examining the likely consequences of inaction or any of the most probable paths forward being proposed in the United States and European Union.

In order to effectively dive into the current policy dilemmas around Net Neutrality, it is important to contextualize our understanding by examining the realities presented in the following four graphs.

The first one shows the growth of the average rate of internet download bitrates since 1985. While it appears at first to be a straight line, looking at the left column you realize that it in fact represents exponential growth; the kind of growth which would be impossible to map on a fixed increment scale. The technological progress represented is important to keep in mind as it reflects the fact that a combination of technological development and market forces will continue to drive significant speed increases over the foreseeable future. Based on this largely undisputed trend (even the most staunch Net Neutrality advocates do not suggest that speeds will move backward in the medium to long term, just forward more slowly), if internet service providers (ISPs) are granted the right to provide varying levels of speed, all speeds will still increase from today’s rates.

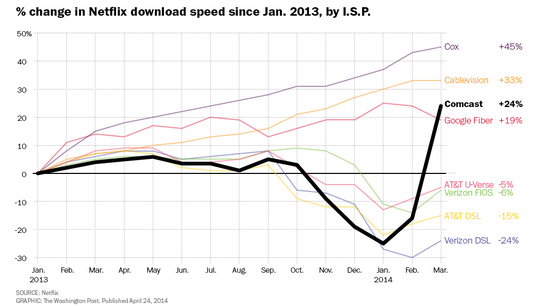

The second graph shows the Netflix-reported percentage change in download speeds in the United States since the beginning of 2013 (a similar graph was unavailable for the EU). Netflix is a significant player in the Net Neutrality scene, and therefore worthy of closer examination, for three reasons.

- It is responsible for over 30% of American internet traffic during its peak-use times, the largest amount of data delivered by any single company. As the service expands in the EU there is every indication that Netflix or one of its streaming video competitors will come to play a similar role

- It is one of the largest companies in favor of net neutrality

- Seemingly contradictorily, it is one of the largest companies which has agreed to pay for preferential access to data delivery speeds

The interesting and important point made in the graph above relates to Comcast, an ISP that Netflix says has pressured it to pay for faster access with which to deliver its services. According to Netflix, the company began talks with Comcast in January and signed a contract in February, at which point its data speeds over their network jumped from some of the comparative lowest, to some of the highest. Netflix argues that this shows the unfair power being wielded by the major ISPs, and the need for regulation which will enforce equal access to content delivery.

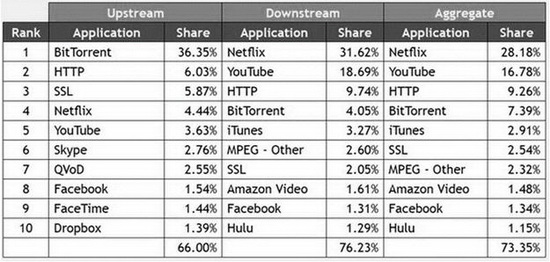

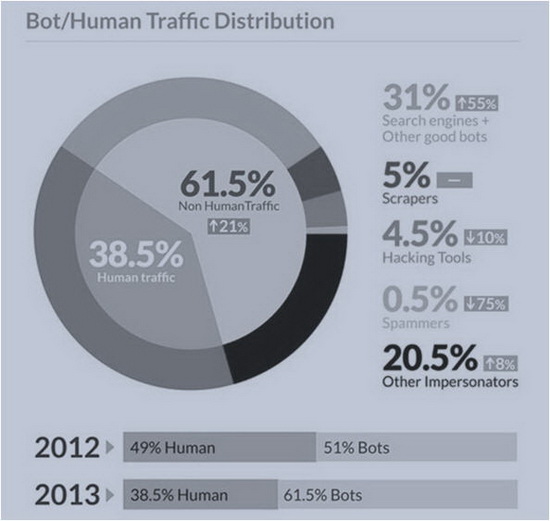

The third graph spells out more clearly the percent of bandwidth being consumed by the ten most data heavy content providers. It must be approached however in conjunction with the fourth graph (below) which demonstrates the growing portion of overall traffic which is made up of non-human bots and engines which access sites/content automatically. It quickly becomes clear why the ISPs feel that they have the right/responsibility to control net traffic in order to optimize user experience (large data users like Netflix and Youtube slow down the rest of the internet if all other things are left equal because of the strain put on limited resources), but also the opportunity to increase their own balance sheets by skimming from some of the riches companies operating not just in the space, but in the world. Google for instance just this month surpassed Exxon to become the second richest company in the world, while Netflix recently cracked the Fortune 500 with a 26 billion stock valuation). Martin Geddes, a telecoms consultant, argues that many advocates of net neutrality are ignorant of the technical basis of the internet and the potential to improve it. “The basic problem with net neutrality is that it assumes that non-discrimination between packets will result in a fair and efficient outcome for users,” says Geddes. “This assumption pervades the academic literature. However, it is untrue. By neutralizing the legitimate resource allocation role of the ISP, it mismatches supply and demand. This creates worse experiences and higher prices for end users.

There are many reasons that government plays a role. The primary among them is perhaps the fact that in most developed countries, the majority of spectrum and hardware that ISPs use to deliver content is either leased or built-out based on contractual agreements with the national government. In the United States for instance, the right to build infrastructure was largely bestowed after auction processes which granted winning bidders with both the rights to commoditize, but also a variety of responsibilities regarding availability, speed and access provision relevant to the portion of the spectral/physical network space they won.

These contracts often last for decades, and therefore many of the rules and regulations which originally governed them are outdated either because they first applied to other forms of service entirely (such as cable or landline telephone connections), or because they were created in the early days of the internet when the future of the technology was near-impossible to comprehend. Because of this, the battle that is now being waged regards not whether the currently enacted net neutrality principals should be weakened, but whether, given the lack of much specific regulation in the matter, norms should be established period.

Traditionally discretion regarding the build-out of services and charges levied on customers was left mostly in the domain of the telecoms, with the idea that competition would be enough to ensure that customers received an affordable and beneficial end-use experience. Governments however retain some degree of power over regulating changing use of infrastructure, and near total power concerning how future allocations are managed.

The war that is being waged now is not over whether the currently enacted net neutrality principals should be weakened, but over whether, given the lack of any specific regulation in the matter, norms should be established and to what degree. Traditionally the right to build services and charge customers was mostly left in the domain of the telecoms with the idea that competition, however limited, would still be enough to endure customers received an affordable end use experience. Because government has assumed the role of authorizing and incentivizing this sort of infrastructure grown, it retains some rights over how the current allocations are managed and complete rights over future development and expansion in the sector, especially when it comes to new technologies that arrive to compete.

ISPs say that without the money they could be making from charges placed on service delivery, they will not be able to upgrade the networks optimally, that progress will be made, but at a much slower point than if they had access to more money

One of the most persistent fears of those in favor of net neutrality regards the potential of service providers to not just charge the most flagrant users of their infrastructure, but everyone. ISPs argue that competition is enough to ensure that this will not happen, and that without the money they could be making from charges placed on service delivery, they will not be able to upgrade their networks optimally; that progress will be made, but much more slowly. Neutrality advocates argue that in the same way your average citizen does not think of buying a radio station, so they would become ever less likely to buy a website or create an online startup, or any of the many other content ventures which currently make the internet the relatively democratized and equal-access experience to which we have grown accustomed.

It is obvious that governments have many forces pulling at them, as well as many options to consider. A second article will focus on some of the primary alternatives being considered in the United States and European Union, as well as on their potential consequences.

.

.

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked with *