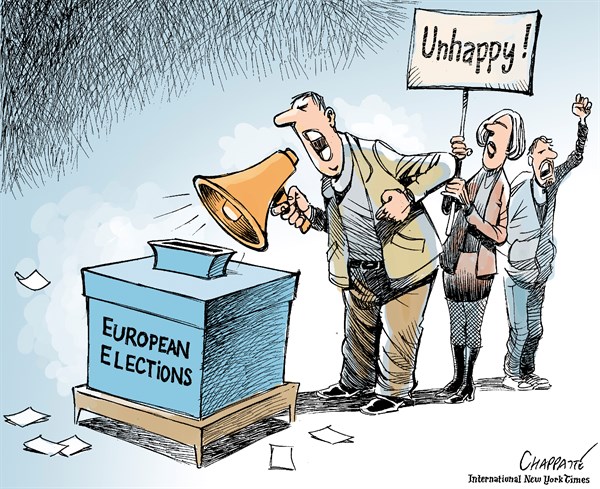

Dealing with the legacy of 2016, 2017 started off as a very uncertain year. Adding to this, four of the founding countries of the European Union will have to go through general, presidential and federal elections. As the optimistic predictions on Brexit and the US went terribly wrong, it is now time to consider what could happen if populism won.

The future of European unity relies, for a good part, on the electoral choices of Germany, France, the Netherlands, and perhaps Italy. The populist threat deriving from their outcome could have enormous implications – in terms of national politics, economics, and, naturally, European policy-making. Migration plays an undeniable role in the shaping of electoral campaigns throughout Europe. Not a major change, one could argue, if compared to 2016, as migration remains the hottest debate topic politically. Now, however, it will also be a pivotal point of reference and deciding factor for those called on to vote.

If we look at Brexit, we can argue that anti-refugee arguments won over voters, even though fighting migration was not the only core point of leaving the EU. If we look back at Trump’s campaign, the migration issue was used even more, and in a way to convince the electorate that many national, internal problems are traceable in “illegal immigrants”. These two turning points of 2016 can both confirm that migration, and how it is handled by politicians, has an influential power over voters.

The roots of such influence might be found in the increasing disappointment with liberalism, intensified by the economic crisis, the latest refugees’ influx and at the same time the atrocious terror attacks in Europe. In any case, migration ends up in a box full of arguments that are often not related. The most recent example of this trend is the Italian referendum, supposedly on a constitutional reform. Since Renzi mistakenly announced his resignation in case of defeat, the referendum turned into a vote against the government and, for the far-right party Lega Nord, a vote against “uncontrolled immigration and the destructive migratory policies of the EU and the Democratic Party”. This, however, fails any logic.

Even though general elections have not been officially settled for this year, Italy is deemed to be the most dangerous country – in terms of voters’ choices – by the markets. Next to the far-right there is in fact another anti-establishment and anti-euro party, with a higher possibility of winning, i.e. the Five Stars Movement. If these parties won, as put by the Wall Street Journal, the unpredictability of their governing is the real challenge for Europe, rather than elections per se.

What is certain instead, is that other key Member States will be voting soon: the Netherlands in March, France in May and Germany in September 2017.

The People Party for Freedom of Wilders uses Islam as a ‘hot-botton issue’, arguing that refugees would undermine European values and identity. The possibility of entering a parliamentary coalition is however lower and less dangerous if compared to France. By distancing herself from her father, Le Pen gained more popularity and, due to the terrorism challenge the country faced over the past years, the topic of migration is linked here to a widespread sentiment of fear. At the same time, the left has no real leader nor alternative to offer. A similar situation characterises Germany where – even after the candidacy of Schulz – Chancellor Merkel still seems to have an advantage and where the real fight is between her CDU and the right-wing populist Petry’s AfD, which hopes to get 14% of votes, managing to enter the Bundestag for the first time.

If we imagined the worst case scenarios (where all these parties won or obtained a good majority to act in the government), what would this mean in terms of migration policies? These leaders have not yet planned to build proper Trump-style walls, although fences have already been raised at the outskirts of Europe and the Common European Asylum System has already taken a stricter direction. Also, the people of these countries could feel more legitimate than ever to perpetrate hatred and demonstrations against refugees. Though, it is right at this point that we will have to remain more united to protect our rights and freedoms. And even if these negative predictions are not realised, we should not consider ourselves safe. Unlike the UK and the US, we need to be prepared to the possible advent of a new populist era and the traditional parties should voice the concerns of all the voters especially on migration issues, without letting these at the mercy of the far-right.

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked with *