Despite having achieved an unprecedented decrease of Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions within its territory, lowering them by 13 percent from 1990 to 2010, the European Union’s carbon footprint has increased by 8 percent during the same period. This paradoxical phenomenon is the result of our increasing demand for goods and services, which is mainly satisfied by importing products from developing countries that typically have more carbon-intensive industries.

There are, in other words, high emissions embodied in international trade that accompany the flows of products from the point of origin to the point of consumption. The most characteristic example is the case of China, where one-third of its GHG emissions are associated with the production of goods that are exported and consumed in the global north.

As a result, the reduction of EU’s emissions could be proven futile since its residents fuel the production of ‘dirty’ goods, which increase GHG in the atmosphere but merely in another part of the world. This shows with the most prevalent way the necessity to regulate not only the production of GHGs, as EU very successfully already does, but also the ‘consumption’ of emissions.

Currently, when GHG emission targets are being discussed, they are following the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) guidelines, which allocate emissions according to the principle of geographic responsibility, meaning that the emissions are assigned exclusively on the countries that release them. This Production-based (or territorial) accounting, though, fails to address the impact of trade on global emissions.

The most prominent alternative that holds consumers accountable for their demand for domestic and imported goods and services is the use of a Consumption-based (CB) accounting. According to this approach, the GHG emissions occurred in the course of production and distribution of goods are attributed to the final consumer of these goods.

An example that illustrates the difference between these two approaches is the production of a smartphone, which in order to be sold as a final product requires the extraction of ores and elements from different parts of the world and every stage of its manufacturing process takes place in a different country. Both resource extraction and the manufacturing of the smartphone’s components are considered highly energy-intensive and often polluting processes, which result, among others, in higher GHG emissions than if it was produced within EU’s borders.

Under both Production-based and Consumption-based accounting, the way of estimating the emissions remain the same, but the difference is spotted in the allocation of responsibility, which in the latter case is attributed to the country where the smartphone is sold.

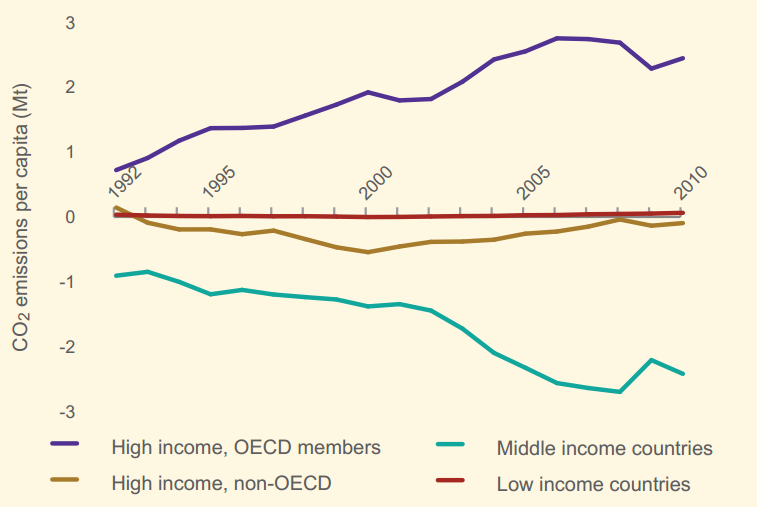

If a consumption-based accounting was to be adopted, the view of who has the greatest impact on climate change would have been completely different. As shown in Figure 1, from a consumption perspective, high-income countries steadily increase CO2 emissions while middle-income countries are lowering their carbon footprint, in contrast to what has been a common belief that middle income countries, like China and India, are the main contributors to a large share of GHG emissions.

Figure 1. Total net imported emissions from 1992 to 2010 (imported minus exported CO2 emissions).

Source: Dawkins & Croft (2017), adapted from Eora Database.

Using a CB accounting would give EU the opportunity to track its residents’ unsustainable consumption of products in a more efficient way and address this issue in a more comprehensive fashion. Another significant advantage is that, in the international level, more GHG emissions will be covered by the environmental policies developed by the EU.

This is mainly because it will help incorporate the scope of international climate policy into the export sector of the developing countries, and that it will deal with the increasing problem of ‘off-shoring’ emissions that occurs when developed countries relocate their manufacturing base to developing countries.

EU officials, such as Jacqueline McGlade, the Former European Environmental Agency Executive Director, have stressed the importance of mitigating the unsustainable consumption patterns of EU residents. Also, in the end of 2013, EU initiated the Carbon-CAP project, which aimed at providing information and evidences on CO2 emissions related to consumption of products within EU borders and stimulating a policy mix that addresses both the consumption and production side of GHG emissions.

In 2016, the project concluded that there is an urgent need for EU to start recognizing and quantifying the emissions embodied in trade if the Paris Agreement targets of keeping the increase of temperature below 2°C is to be achieved.

However, EU’s research has been at odds with its decisions, since almost a year has passed and to the best of my knowledge there are not any actions taken to incorporate consumption-based accounting of GHG emissions in its environmental policy-making.

There could be many explanations why EU has been reluctant to adopt such measurements. For instance, a CB accounting would affect EU’s image as a global leader in the combat of climate change, or it might indicate a different policy mix that would be less welcomed by its residents, since it would pose restrictions on the imports of cheap products.

Also, there would be considerable challenges in implementing this approach, since such schemes are more efficient when the global community is willing to accept them.

That said, and considering that CB accounting represents an invaluable tool that can steer policy measures towards the root of the problem, it seems that there is only one meaningful way forward for the EU. This is to advocate for and foster the use of Consumption-based accounting in the international climate negotiations, while making efforts to quantify the impact of its own consumption on the environment.

1 comment

1 Comment

Roland Gilmore

22/07/2017, 10:04 amGlobal warming as a result of GHG emissions will pale into insignificance as the Grand Solar Minimum takes hold over the next 3 years. This will result in reduced harvests, increased food prices and subsequent famine. As a result of cooler conditions and unseasonable weather, we are already seeing reduced harvests and increasing market futures prices across North America, Europe, Russia and Australia.

REPLYRecord low temperatures are not being reported in the same way that record high temperatures are. A new coldest temperature of -30 C was recorded in Greenland this month while snow and ice build up exceeds the well publicised melt. Similarly, ocean warming and the build up of snow and ice in east Antarctica more than offsetting west Antarctica losses has not been reported either.

Despite official denial, geoengineering of weather is a reality and the earth’s protective ozone layer is being “shredded” as a result leading to an increase of 15% more UV reaching the earths surface than 2 years ago. As our sun “goes to sleep”, the electromagnetic protection the earth enjoys will weaken leading to increased cosmic radiation reaching the earth’s surface.

Indications of accelerating migration of the earth’s magnetic poles that could lead to pole reversal that we know has happened many times in the past is a far greater threat to humanity than CO2e.