African states have performed dual roles producing refugees while offering asylum to others. However the economic status of many receiving countries is too low to support provision of adequate basic services to their own citizenry and refugees are perceived as an extra burden. Civil society organizations have therefore taken on provision of vital services to fill this gap, complementing the work of UNHCR, the body mandated to safeguard and protect the rights of refugees.

At the moment, the number of asylum seekers comprising of refugees and other persons of concern in eastern African have surpassed the two million mark and still counting. The largest numbers are found in Ethiopia and Kenya with over 600,000 registered in Ethiopia and over 500,000 in Kenya. The number is certainly increasing as the Yemeni and Burundi crises continue to deteriorate producing more refugees.

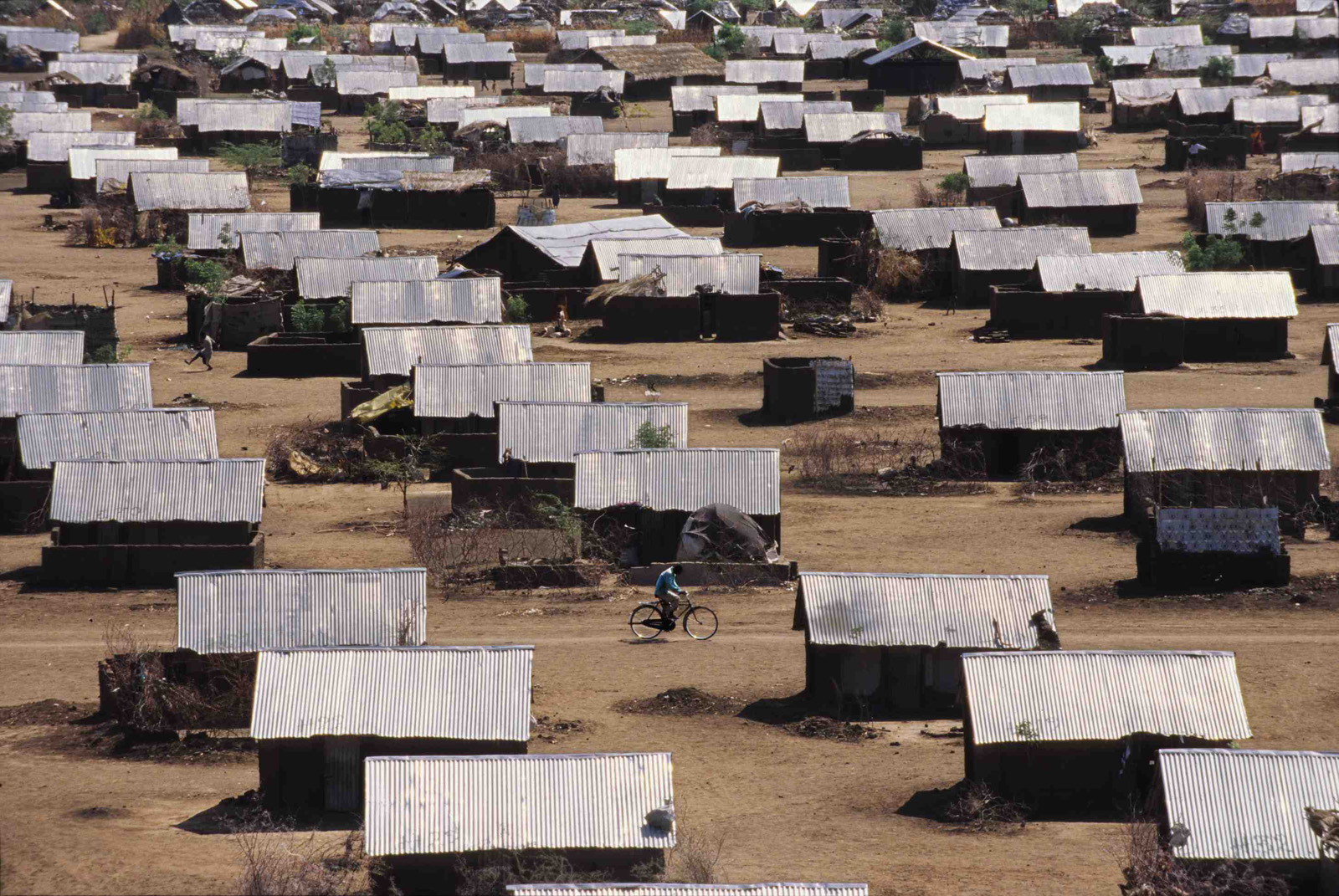

Receiving States especially Kenya and Ethiopia have over the years responded to the increased influx of asylum seekers with policies that promote management of refugees through confinement in camps, with a small number residing in cities and other urban areas. In addition, the same states have made reservations to articles of the 1951 convention on the Status of Refugees, specifically limiting the refugees’ right to gainful employment. It is ironical to imagine even former university professors are wasting away in refugee camps!

The long and short of these policies is that refugees have to be provided with everything they need to sustain their lives. Civil society organizations have mobilized resources mainly from foreign governments and donors to provide access to life-saving services for refugees. The list is long but one vital service stands out – education.

When a country experiences conflict, the first sector that often suffers is education. This is has been the case with South Sudan and Somalia which have not known peace for many years. Before South Sudan gained independence in 2011, she had been locked in a long-drawn civil war with the government of the day, while Somalia descended into anarchy in the early 90’s. As a result, entire generations of refugees originating from these countries have never had any formal education; therefore adult illiteracy rates are very low.

In the camps Kenya, Kakuma and Daadab; Gambella and Dollo Ado in Ethiopia, and in the settlements in Northern Uganda, civil society organizations have responded with unique educational services that respond to the needs of the different age groups. These range from language classes, early childhood and primary education, provision of scholarships, and vocational training and alternative learning for adults.

Positive spillovers of these services to host communities leave a lasting impact especially in locations that are far from government reach. I had an experience of this one time in the remote Maban county of South Sudan where a group of local elderly men were learning English courtesy of an organization that was serving refugees. When I asked them why they were learning English, they retorted that they had never had any chance to undertake any formal learning. Incidentally, the country has also made a policy decision to use English in place of Arabic as its official language.

It is important to note that educating refugees has both short-term and long term benefits. In the short-term, it eases their integration in the host countries while a long-term benefit is that it prepares them to positively contribute to their own countries once they return. A case in point is South Sudan whose civil service has a number of senior staff who benefited from education scholarships obtained in countries they had sought asylum in before they repatriated after independence in 2011.

Another important contribution has been advocacy for favorable legal and policy frameworks in the region. Kenya’s Refugee Act of 2006 was a culmination of many years’ of concerted efforts by agencies serving refugees in the country. Subsequently, the civil society has managed to tame use of unfavorable policies by government to some extent. While the same cannot be said in some of the other countries due to policies restricting advocacy work, the continued presence of civil society organizations is a testimony of their valued contribution to those countries.

However, all is not rosy anymore as foreign funding is quickly dwindling and projects are downsizing. UNHCR’s budgets have also in the recent past experienced huge deficits too. New innovative funding strategies must be found otherwise refugees will be left without vital support.

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked with *