Economic governance reforms and Eurozone consolidation has significant institutional and political consequences: a multiple-tier integration is ever more realistic. „Out” countries seek to mitigate the negative impact of these developments. In this respect V4 – Visegrad countries differ a lot: Slovakia, a relative latecomer in economic reforms is part of the currency union. Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic are not Euro-members. But even this sub-group is divided: Poland intends to join whenever requirements are fulfilled while the Hungarian and the Czech governments are cool on accession. At the same time, further economic federalisation in the Eurozone is to come. Against this background, the question whether a long-term “great divide” among V4 group countries in relation to their EU policies and consequently their future situation in the rapidly altering EU will be maintained, is of key importance.

European economic integration in political perspective

Economy and politics walk hand in hand in the process of European integration. This has been clearly seen during the years of the euro crisis. During the worst crisis ever experienced by the EU as from 2008, the euro was not seen as the solution, rather than the source of the problem. But in fact, the true lesson from the recent malaise is that the institutions and policies behind the common currency need significant reinforcement.

The euro is one of the most sophisticated results of the process of modern European integration. It is also a symbol of peaceful collaboration between European countries, which has been accompanied by, or has resulted in, unprecedented levels of peace, stability and prosperity in Europe.

In order to restore confidence in the single currency zone, a more coherent fiscal union must be created, which will require further measures of economic integration in the long run, such as the creation of a European finance minister, a larger EU budget, and a fully operational banking union. Tax and even social policy coordination will also be on the to do list. Obviously not all members will be able or willing to go that far. EU members states are destined to go at different paces maybe even in different directions. A two-speed Europe has already come into existence in reality which was reinforced with the UK’s decision to stand aside. The dynamics of integration is uncertain. This is partly because the alliance between the 18 current members of the euro zone is not a stable formation per se; for many of them, the bar will be set too high, and they will not be able to accept the degree of harmonisation needed. An additional factor is that integration is to proceed on an intergovernmental – rather than supranational – basis, and there will be a need to clarify the roles of the EU bodies, in particular that of the European Commission. These developments have consequences for the V4 Group as well in the medium term.

One has to be aware of the fact that despite its undoubted successes, modern European integration – in historical terms – is a fragile construct. The main reason for this is the absence of a precise self-definition. Europe seems still to be a nascent formation, consisting of political compromises, a common system of law, a common economic zone, and a collection of political and institutional responses to crises. Although the peoples of Europe have lived side by side for thousands of years, they do not share traditions, living myths, a common identity or language; nor do they project a single image towards the outside world. The political class and the intellectual elite are just as divided: some want more Europe, while others think that even the present level of cooperation is far greater than desirable. The underlying reason is that no one has a clear picture of the function, goal and future development of the EU; there is no agreed vision.

The federalist school holds that the time has come to establish a political union, or the alternative is a collapse of the integration project brought about by the euro crisis. Others claim that political union is not only unnecessary but also impossible in Europe[1]. Many member states, much of public opinion and of the European cultural elite reject the idea of a political union. In addition, Europe is not yet prepared mentally for such a union. There are three reasons for this. First, the lack of common European traditions, identity and language. Second, the member states having extremely divergent visions for the European Union and holding a variety of opinions on what is the ideal economic and social model. Third, it is a physical impossibility to create a unified political union out of a Europe that has 28 members and is expected to expand continuously. Consequently, the result is a multi-speed Europe.

The UK is distancing itself from integration, thereby creating a good reason for the German-French duo to press on with moving towards Core Europe while avoiding the EU-28 setup as it is today. For eurozone key countries surrendering more of their sovereignty will be far less painful than a euro meltdown. Chancellor Merkel seriously believes that the demise of the euro would be the downfall of the EU.

By creating the euro (which was in many – especially in economic – respects either an irresponsible enterprise or a visionary act, depending on one’s perspective), Europe crossed the Rubicon: it pushed integration to a point of no return where it either presses on with a fiscal and economic union or must bear the dire economic and social consequences of a break-up of the common currency. As Ottmar Issing puts it: Der Euro “is still an experiment whose outcome seems likely to remain uncertain for a considerable time to come.”[2]

Euro-related challenges are not the only factors: Europe at the beginning of the 21st century is facing not only a financial crisis but also a political crisis (caused in part by the economic crisis). It is a political crisis in the sense that the political institutions established after World War II, including those of the EU, have lost the confidence of the electorate. Society and the economy are undergoing rapid change. For many, such change is an opportunity, but for even more people it is a threat. This undermines society’s confidence and leads to the chronic rejection of political institutions and a widening of the chasm between the elite and the man in the street. The welfare model that was designed to prevent a repetition of the disastrous social problems of the interwar period is now in a crisis, thereby jeopardising the social peace that was based on keeping the middle-classes satisfied. This in turn has added to economic and social tensions caused by immigration and to a hysterical fear of globalisation. In the view of many, globalisation – or as the anti-globalists call it: the unbridled competition of dog-eat-dog capitalism – finds embodiment in the European Union. It is therefore not accidental that there is a growing rejection of European integration, accompanied by a general rejection of the political mainstream.

Crises are inherent to capitalism, but the crisis that began in 2008 has several unique features. The first is its rapid spread in the financial sectors of the developed world, which was due to the unprecedented interconnectedness of the world’s financial markets. Many have drawn comparisons between the current crisis and that of 1929. True, at that time too, an irresponsible deluge of credit had caused economic bubbles, but the crisis was one of over-production. In other words, the problems of the 1930s originated in production, i.e. the real economy. In contrast, the crisis of 2008 originated in the financial sector. There were no problems with the foundations of the real economy until they were rocked by the financial meltdown. But the most important feature of this crisis is that – contrary to previous ones in the second half of the 20th century – it is a crisis of the West. The scenario is not that of a collapsing emerging economy (Argentina, Mexico, Russia, East Asia) that has proved itself incapable of implementing the operating principles of Western liberal capitalism. On the contrary, the rest of the world remains relatively stable while the economy of the West (USA and EU) seems to be cracking. Ground zero of the financial crisis was in the United States, the key archetypal capitalist actor. However, by 2011, the eurozone had become the real focus of the crisis. China, Japan, and the United States are keeping a watchful eye on the success (or failure) of Europe’s crisis management, while drawing up various strategic scenarios. Thus the crisis has crossed the Atlantic, and made the leap from the financial sector to the real economy, affecting in particular national budgets. Act two of the current crisis centres on unsustainable national budgets. This explains why, in Europe, a rescue is needed not only for the banks but also for the member states.

Clearly, the present crisis is one of the most serious ones in the history of European integration. It is fundamentally a political crisis rather than a purely economic one. It is the consequence of a downward spiral of political and economic problems that mutually reinforce each other. At its centre lies a weakness of political vision in the EU and in the eurozone. In economic terms, Europe is better placed than the USA (when one considers the level of national debt or fiscal deficit); yet it is the eurozone that has become the epicentre of the crisis. History teaches us that monetary unions are unsustainable without political coordination and a fiscal union: a major economic crisis has now made this painfully clear to the eurozone too.

In the history of European integration, crises have acted as the triggers of major political and institutional changes. Europe and the EU face many external and internal challenges, the scale of which has grown in recent decades (greater international competition, a whole series of demographic, social and budgetary problems). Member states have often made feeble and belated responses to such challenges with delayed reforms and poor management of immigration and demographic trends. At the same time the European Union has not been more robust either (see weak and eventually failed policy visions as the Lisbon programme, diplomatic and geopolitical difficulties due to the lack of a common EU position, years of impasse after the failed European constitutional project, etc.)

The question is whether the present crisis, which threatens the existence of the most important achievement of European integration – the common currency – will lead to a ‘quantum leap’ towards closer political integration and a multi-speed Europe. It may indeed result in any of the two.

In the medium term, the whole of Europe must prepare itself for a decade of sluggish economic growth. The gap in economic, social and political development within the eurozone will only widen unless there is a major change of direction in the integration process. In the long term, the European welfare state is unsustainable in its present form (cf. ageing and shrinking populations, budgetary over-extension, an increasing competitive disadvantage vis-à-vis Asia). For this reason alone, it would seem sensible to pool European resources and to aim for a common European political and geopolitical agenda. But that will be the result of economic necessity rather than rationality.

In this socio-economic context a lot of discussion is taking place about European political union. But one thing has to be clear: not any form European political union should or could mean the formation of a regional world government or the elimination of Europe’s nation states. The nation state is a European invention, and Europe’s nations will never be dissolved into an all-embracing pan-European political unity – if for no other reason than because for Europeans a sense of European identity barely exists, and Europe does not have a common language like the United States does. Political union could mean closer political integration, a real common foreign policy, a real European (or Eurozone) president, real European parliamentary elections, a real (perhaps eurozone) budget, and a truly common economic policy. It could also mean unified European representation (a single seat and a single voice) in international organisations as well as stronger pan-European symbolism in daily life. The euro would still not be backed by a real country, but there would be regional integration with a far stronger political profile.

Currently, the key question concerning the future of European integration is whether or not a currency without a country is viable. The European Union has tried to establish a monetary union without a political union, but it has become increasingly clear that both are needed – or neither. Some thought that this ambiguous situation would lead to a great crisis, forcing the EU to establish closer political integration. That is to say, what cannot be achieved through nice words, will happen under pressure – as has been the case so many times before. Angela Merkel has a point saying that if the present crisis leads to the end of the euro, this would result in the collapse of European integration as a whole, at least in its present form[3].

Not only is the common currency without a country; it also has no backing in the form of political institutions or even the basic foundations of economic integration. The EU barely has a budget: in a modern market economy, the budget amounts to 40-50 percent of GDP, while the EU budget amounts to just one percent of European GDP. Moreover, money is not spent on things that a “normal” budget would target, but for very different purposes, such as farm subsidies – which still account for almost every second euro spent. These factors add up to a budget ill equipped to make significant transfers between eurozone members at different levels of development and in different stages of the economic cycle. An even more important deficiency of the eurozone is its lack of a common economic policy and the cumbersome decision-making with unanimity required, for instance, to adopt common fiscal rules.

A closer union in fiscal and economic policy terms – a European finance minister, eurobonds, common financial supervision, a closely coordinated economic policy – seems inevitable, as does, in certain respects, a political union. All this will require a new treaty, an amended ECB statute, and above all political will. Closer integration may certainly be envisaged in the form of a multi-speed union. A radically different European space is appearing before our very eyes. And in this new space the role of Europe’s major powers will change, and there will also be a shift in the relative clout of countries. Germany may be the greatest beneficiary of the reshuffle with its new-found regional primacy. German political elite supports closer integration, which will help mitigate fears of German hegemony, but the German-French tandem is no longer regarded as a partnership of equals. History (and necessity) has made the economy – and the common currency – the driving force of federalism, rather than political institutional development or the construction of a European cultural identity, which would have favoured the French. The French wanted the euro – and the whole process of integration – as a means of keeping the Germans in check, but in reality the opposite happened. The principles of France’s European policy – the multiplication of French power and capacities at the European and global level coupled with categorical inter-governmentalism – have been sorely wounded.

Historically speaking, hostility, rivalries and war are the norm on the European continent; periods of peaceful co-existence are the exception. Or, as prof. Anis Bajrektarevic rightfully questions our deceiving wonderworld: “Was and will our history ever be on holiday? From 9/11 (09th November 1989 in Berlin)… to the Euro-zone drama, MENA or ongoing Ukrainian crisis, Europe didn’t change. It only became more itself – a conglomerate of five different Europes”.[4] Also, in historical terms, modern European integration (voluntary cooperation between sovereign states, based on the respect for common laws, and which was launched after World War II with a strengthening of economic and commercial relations but with the primary purpose of pacifying Germany) is a vulnerable formation. As a consequence, peace and solidarity on the European continent may soon be replaced by growing hostility – if the economic situation deteriorates and becomes crisis-ridden in a geopolitical milieu that is increasingly unstable. The fate of the boldest achievement and symbol of EU integration – the common currency – is intertwined with the fate of integration as a whole: an anarchic collapse of the euro would be accompanied by the break-up of the EU and political paralysis in Europe. The euro is fundamentally a political and symbolic creation; in its present form, it does not have firm economic foundations. In light of the above it is in the interest of the EU to save the euro by establishing a strong economic union. With its present architecture, rules and stakeholders (whether they are the EU-28, the EU-26 or the EU-18), the European Union is incapable of moving forward at the right speed and depth. In addition, European public opinion gives a cool reception to any initiative coming from above, from Brussels. The European Union – it seems – faces two possible scenarios in the long term. Under the first scenario, it passively allows the centrifugal forces (markets, member-state sabotage, public disinterest) to break it up or it ceases to exist in its present form, with the unplanned termination of the euro. All of this would be temporarily accompanied by an extremely grave crisis. Under the second scenario, in the extended lands of Charlemagne a new intergovernmental treaty may be adopted, resulting in strong economic policy integration and preserving the euro. The second and third groups of countries could join later based on new conditions (which would be far stricter than they are today). The historical and European lesson is that regional integration projects are far from everlasting, and often the temporary break-up of a poorly designed form of integration is the key to a restructured formation that guarantees long-term survival. Historical experience shows that monetary unions are successful when they have among their members at least one economic power-house acting as the engine. Central institutions are also needed to control and enforce the rules. The most successful ones are preceded by a political union, as in the case of the USA, the UK or Germany. Price and wage flexibility is a fundamental criterion, so that wages can be limited in poorly performing regions, just as inter-regional transfers can be useful. Fixing and applying criteria on economic convergence also prove to be necessary. In the eurozone, we can hardly talk about real flexibility of labour markets, just as we cannot talk about a political union either. The EU budget is not designed for major income transfers either, as it only disposes of 1% of GDP. The US federal budget is around EUR 3.3 trillion, compared with the EU “federal” budget of roughly 140 billion euros, a good part of which is transferred to non-eurozone countries. The difference between the internal transfer capabilities of the two monetary unions is obvious. In any case, the euro was created by politics. Politics must also help preserve it. As André Sapir and Jean Pisani-Ferry put it: the euro area needs fewer routine procedures and more ability to act in times of real crises[5].

This is the economic and political framework in which V4 countries (Hungary, Poland, Slovakia, Czech Republic), deeply integrated in the EU’s internal market and in the case of Slovakia as member of the Eurozone, should navigate.[6]

The case of the V4

The close link between economy and politics has been clearly demonstrated during the years of the euro crisis when the euro was often not seen as the solution, rather than the source of the problem. But in fact, the lesson from the recent malaise is that the policy system behind the common currency needs significant reinforcement. The way V4 countries approach the Euro accession and crisis management is also a mix of economic and political features.

Firstly, a few remarks on the V4 Group itself. The loose alliance of the four central European EU member states, namely Hungary, Poland, Czech Republic, Slovakia until introduction of the “double majority” voting in the EU in late 2014 had equal number of weighted votes with Germany and France put together. If counted as a single nation state, V4 with its sixty four million inhabitants would rank 22nd in the world and 3th in Europe. Moreover it is the seventh largest economy in Europe and the 15th globally. The Group had a significant blocking, therefore policy-shaping power in the EU. The V4 Group functions as a leverage of influence for their members not only in Council voting but also in diplomatic dealings. Chinese, Turkish, or Indian political leaders have been much more open to contact the Group as opposed to deal with members individually. V4 has also gained a certain appeal in the eyes of other countries in the region, but the alliance wanted to keep its doors closed until now[7].

From November 2014 though, the double majority replaced the current weighted voting system. According to the new rule the support of 55% of the Member States representing 65 % of the overall population of the European Union will be required. The new system significantly modifies the power distribution by strengthening the influence of big Member States – with a population of 60 million; Spain and Poland will lose their big Member State status and medium-sized countries’ – between 2 and 11 million inhabitants – voting power will be reduced dramatically. Germany and France will gain increased blocking capacities but V4 countries will not be able to form any blocking coalition any longer. Even the new Member States joined in 2004 and 2007 will not be able to block decisions under the new system. So with the new voting rules, plus and more importantly the largely diverging visions on decisive European issues, and with some of the states in some out of the Eurozone, and especially with Poland with way more significant geopolitical ambitions and Hungary’s political isolation (more on these issues later) the V4 cooperation will probably get less and less relevant.

As a start it is obvious that these countries are integral part of the European economy with Germany playing a key role as export and import market.

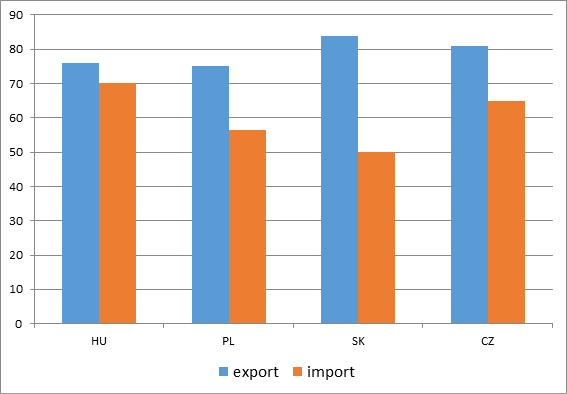

Table 1: Share of EU in V4 countries’ export and import

Source: WTO

The above table clearly shows the deep integration of the V4 countries in the EU market, especially on the export front. As far as import is concerned one has to bear in mind the fact, that these countries are dependent to a great extent on Russian energy sources which shows in the overall geographical distribution of imports

Differences: great divides to stay?

But homogeneity seems to stop here, since the success rate of the V4 countries harnessing the benefits of EU membership differs a lot. Some of the new members were more successful than others in using EU-accession as an economic and modernisation leverage by halving the number of people living in poverty and raising the per capita GDP by almost fifty percent. Bratislava, and Prague is richer than Vienna and Budapest also comes close. This is in itself a spectacular development[8]. At the same closing the wealth gap and decreasing internal territorial wealth gaps in individual V4 countries is much less of a success story in the case of Hungary and to a lesser extent in all the four new member states, although there are major differences in this respect.

Different development paths walk hand in hand with different policies, which indicates that economic success and political decisions are interlinked to a great extent in the region. This linkage seems even more pronounced than in the case of old member states. This stems from the fact that politics in general and the direction in which the political class wants to direct the country is more important in this region in terms of end results both in political and economic terms. A new government in the V4 countries can have dramatic impact on the geopolitical, EU-political and economic policy path the country takes. Long-term political stability is still in nascent form, or in a more pessimistic tone: is a rarity in the region. This is due to lack of self-conscious civil society, stable institutions and as a result: a hyperpuissance of the political classes.

There is obviously a clear difference in the group when euro-status is considered. When it comes to EMU issues, the four countries are in different position and have differing views. But this is only partly justified by economic factors or by the fact that being in or out makes a significant difference. It is also stemming to a great extent from political considerations.

When considering the most important economic trends and features of the first decade of EU-membership of the V4 countries, growth, competitiveness, per capita GDP and obviously the Maastricht-related indicators are worth being analysed. Although one can draw remarkable conclusions from this analysis related to the specificities of the economic development of the four countries in question, the key finding is that Euro-accession is a function of the combination of the existence of the fulfilment of the nominal (Maastricht) criteria, and political determination. They are interlinked and none of the two in itself suffices. Also these two factors will explain the attitude of these countries towards the ongoing and future EU and Eurozone-level EMU reform measures.

In the following section a series of comparative economic data is provided to assess the first ten years of EU membership of the V4 countries.

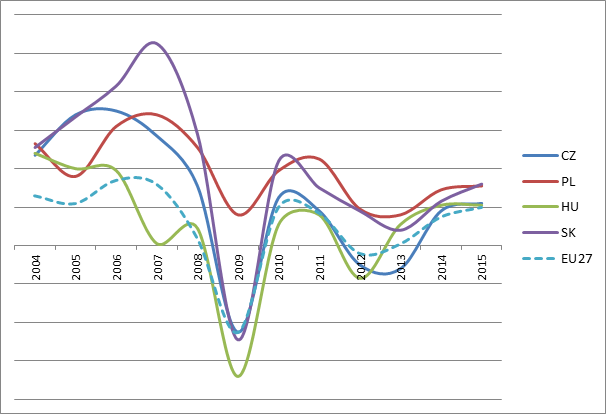

Table 2: Growth rate of V4 countries between 2004-2014[9]

To close the development gap vis-à-vis “old member states” a much stronger economic growth performance is needed over the long run in the V4. The above table shows that basically Slovakia and Poland were able to pull out that performance during the first decade of EU-membership.

The below table somewhat in contradiction to the first one indicates that as regards international competitiveness the V4 countries (including Slovakia) except for Poland are true underperformers.

Table 3: Competitiveness ranking 2003-2014.

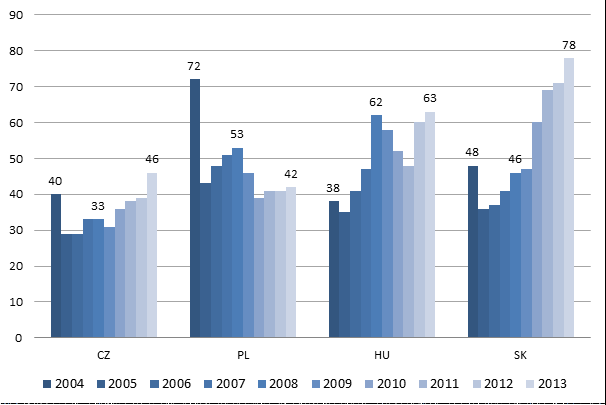

Table 4: Employment level 2004-2013

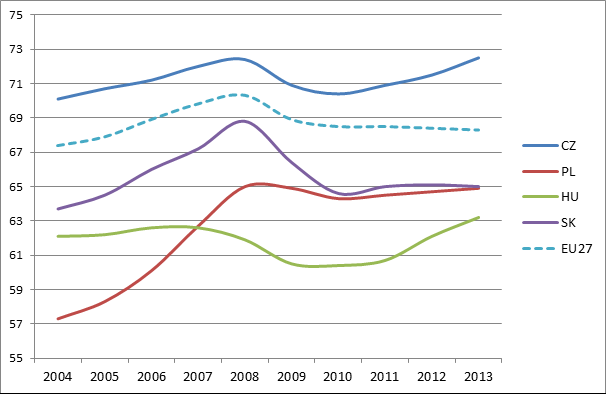

As far as employment level is concerned, where even the EU – including Western European countries – in an underperformer, V4 countries except for the Czech Republic could not even reach the unsatisfactory EU-average.

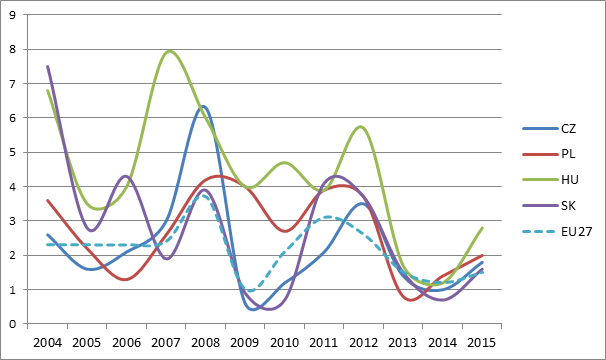

Table 5: Inflation 2004-2014

In keeping inflation under control which is one of the Maastricht criteria the Czech Republic’s and especially Hungary’s 10 year performance proved to be especially poor. Hungary’s performance in relation to the long-term interest rate (another Maastricht criteria for euro introduction) was again the most humble (see below). Not surprising that Hungary is the country that spent the longest period (9 years, between 2004 and 2013) under the excessive deficit procedure.

Table 6.: Long-term interest rates

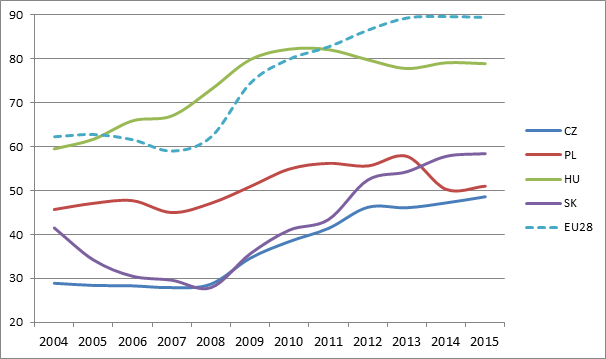

Table 7: Debt 2004-2014.

The EU as a whole and even more so, the Eurozone was heavily hit by the sovereign debt crisis, which resulted in way above the mark national debt to GDP ratios. In the light of this, V4 countries’ performance in controlling the national debt was a relative success, although in absolute terms all of them experienced a rising debt. Here again, Hungary is a relative underperformer with a debt hovering around 80 percent of GDP (although this is lower than the EU average).

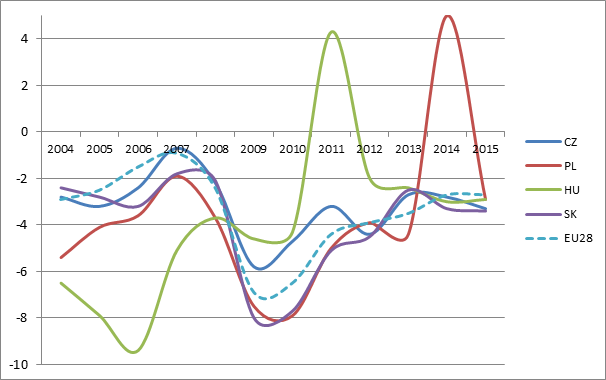

Finally, looking at the most important Maastricht criteria, one sees, that the EU28 average’s and V4 countries’ deficit developed in a correlated way, with a slight disadvantage at the V4 camp. Two outliers stand out: positive balances for Hungary and Poland. But one has to be very cautious with these peaks: they are the results of the nationalisation of the private pension fund assets that later on have been evaporated without either supporting growth or reducing national debt. More importantly the cost of annulling the private pension wealth will be payed dearly by future generation.

Table 8: Budgetary balance 2004-2014

Concluding remarks

In contrast to the nineties and early two thousands when Euro-Atlantic accession was the unquestionable central theme of politics, the V4 countries have started to get separated not only in terms of their economic performance but – and mainly – in terms of their overall EU policies.

Poland clearly aims for a regional power status in the EU and in the Eastern Neighbourhood context, wanting to punch over its weight with the help of a historical reconciliation with Germany and in the absence of France as a capable partner for Germany to shape the future of the integration and with the UK withdrawing itself from the European political mainstream. In this light it is not surprising that Poland is doing everything to be in the potential future core, which necessitates a eurozone membership.

By contrast, Hungary that has manoeuvred itself to a quasi pariah status, with its political freedom fight against the EU and with its clumsy geopolitical rapprochement with Russia, clearly turned its back on the EU, shunning eurozone accession for an undefined period. This rather difficult explain from any economic point of view. Hungary is one of the biggest net beneficiaries of the EU budget, although this country has become a clear underperformer in harnessing the economic benefits of membership. Nor is the anti-EU stance explicable from a reasonable geopolitical point of view since it has resulted in international isolation.

Slovakia the only, member of the Eurozone, experienced a major per capita GDP increase, nevertheless still suffering from territorial inequalities, regularly voiced its discontent with EU and Eurozone (see the issue of the contribution to the Greek bailout) policies and measures, but generally follows the political directions coming from Brussels and Berlin.

The Czech Republic is a cautious EU-partner. Like Hungary it is selective in accepting EU reforms and reluctant to join the common currency. Parts of the political elite voice harsh anti-EU and pro-Russian views. Although the mainstream political discourse is not as militant vis-à-vis ”Brussels” as in Hungary.

What seems to be obvious from the comparative economic analysis is that Slovakia as the only eurozone member does not stand out from the general V4 performance level in a striking way )in fact Poland can be singled out as a success story). This reinforces the fact that Eurozone membership is a function of multiple factors, including political decisions and geopolitical benefits.

In 2014 the V4 group is divided not only by its status (Slovakia in, Poland, Hungary, Czech Republic out) but by its political drive as well (Poland: determined to join, Czech Republic being much cooler, Hungary being even hostile to the idea). This situation also determines these countries political stance related to political decisions relevant to EMU reforms. And – as we saw it earlier – EMU reforms will probably have significant impact on the way the European Union is going to develop not only from an economic but also from a political and institutional point of view. With the reinforcement of Eurozone institutions a deeper divide is expected between the EU18 and the rest. This may be an annoyance to Hungary and the Czech Republic but can be a serious geopolitical concern for Poland that wants to get into the inner circle of the EU to enhance its political and geopolitical clout.

The Stability Pact and the Euro-Plus Pact was not signed by the Czech Republic. The Euro Plus Pact which envisages coordination in areas such as taxation was not signed by Hungary either. A clear political divide is visible here. Is the current political situation a long-term “great divide” in the V4 group? As Hungary and the Czech Republic – without a clear indication of an entry date – leaves the timing of Euro membership hovering somewhere around the beginning of the next decade, this divide seems to be stuck and it will probably deepen as the EU18 will push ahead.

A long-term non-membership has significant economic and political consequences. In exchange of an (often sceptically received) higher level of economic autonomy, out countries lack the firepower of ESM, and ECB in crisis situations. Moreover it is obvious that saving a eurozone country is much higher on the agenda of Brussels and Berlin than otherwise. EMU membership is obviously not only an economic but also a geopolitical or even a security issue especially in Eastern Europe and in the Baltics. Individual countries ponder these factors in a different way. Contrary to the facts that the crisis has tarnished the image of the common currency and that eurozone accession has become a more difficult exercise because of economic tensions and a higher level of suspicion in Brussels and Berlin after Greece had lied itself into the elite club, the eurozone is still desirable place to join. Not only – maybe even not primarily – for economic, but for geopolitical reasons. One of the main drives for EMU membership in the Baltic states is security policy which has gained further relevance since the Russian aggression in Ukraine.

The political manoeuvring of the V4 countries does and will take place in the broader context of how the Europe of 28 will react to the pressing economic and political issues ahead. Member states and EU institutions will have to agree on how to guarantee the long-term sustainability of the common currency, and how take the European citizens on board for this, especially because most of the steps need to be taken will have significant consequences on national sovereignty. The grand design of an institutionalized two-speed Europe that makes room for the UK, and maybe Turkey and Ukraine will also be on the menu. All in all the economic, political and geographical setup of the EU will have to be rearranged and the relevance of being a new or old member state will eventually fade away. But at the same time, the differences between individual V4 countries’ EU policies will remain significant, due to mainly national politics and choices of the political class.

From the above analysis it seems obvious that the choices of the political class in some cases – mainly in Hungary – cannot be based either on proper geopolitical, or on economic considerations. Therefore the research analysis of the V4 countries’ economic policies and general EU-policies should have a strong political economy element. A purely economic policy approach in the research of this topic has clearly reached its limits. A political science and political economy approach should follow up.

First published by www.moderndiplomacy.eu

_____

[3] http://www.spiegel.de/

[5] Pisani-Ferry, Jean, et al.: Coming of Age: Report on the Euro Area, Bruegel Blueprint 4. p.4. 2008, Brussels

[6] M. Nic – P. Swieboda (ed): Central Europe fit for the future: 10 years after EU accession 2014. January 21. CE Policy.org; http://www.cepolicy.org/

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked with *