The LuxLeaks scandals brought to light how multinationals in the EU avoided paying millions of dollars in corporate taxes. A year after, the OECD presented the final package of the international tax reforms discussed previously by the G20 finance ministers. One of its key focuses is the amendment of the IP (intellectual property) regime, such as the patent box regime, so it can create real activity, as opposed to only a way to shift profits for multinationals. The question now is whether the changes will spur growth or not.

This package follows up on the 2013 G20/OECD Action Plan on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (“BEPS”), which identified 15 actions to put an end to international tax avoidance. It aims at providing governments with solutions for closing loopholes that allow “corporate profits to ‘disappear’ or be artificially shifted to low/no tax environments” where no economy translation of these movements takes place.

Potentially harmful preferential tax regimes remain the current concern of the OECD BEPS. A tax regime is considered harmful as long as it answers positively to one of the following three questions: 1) Does business shift activity from one country to the one providing the preferential tax regime, without generating significant new activity; 2) Does the presence and level of activities in the host country not measure up with the amount of investment or income; 3) Is the preferential regime the primary motivation for the location of an activity.

And as it happens, the ousted UK patent tax regime tests positive for question one and three.

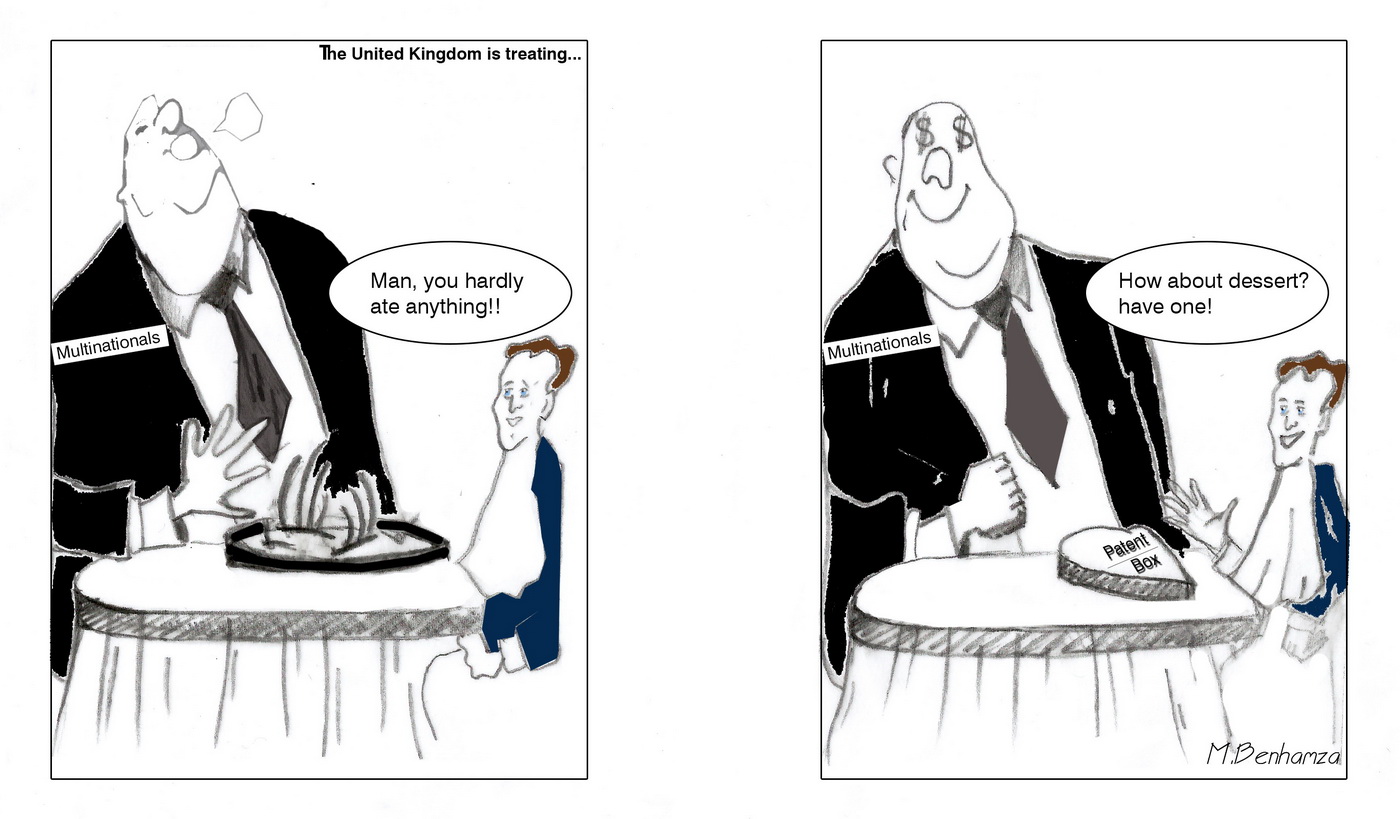

Introduced in 2013, the UK’s Patent Box tax incentive provided a lower tax rate (10 %) to UK companies that were exploiting patented IP (intellectual property) rights. What was first a means to encourage innovation and retain (attract) innovative activities became simply a way for multinationals to shift their patent-derived income from another country to the UK in order to claim tax break. Not only creators of new technology but even owners of patents qualified for the regime, as long as some work was done to exploit the patent in the UK.

Also, the level of tax relief was not linked to the significance of the patent to the product or process. As long as any part of the product was linked to a patent, all the profits arising from its commercialization could benefit from the lowered tax.

This preferential regime came under fire in 2014 prompting an investigation into patent box practices. Things came to an end after Germany – the fiercest instigator of the inquiry, and the UK came to an agreement and drafted a proposal to amend the existing IP tax régime. Namely, a proposal based on the nexus approach.

According to this approach, there must be a direct and genuine link between the income and the activity contributing to that income. This means that income subject to reduced taxes can only be derived from patents that the business has developed or helped develop personally. The current UK Patent Box regime will henceforth close to new entrants by 30 June 2016 and will be abolished by 30 June 2021. On the other hand, the new regime takes place at the same time as entrance closes.

So now that the UK tax regime attracts real activity, it should support growth and innovation. A country has two reasons to introduce a patent box: encouraging innovation or attracting (retaining) innovative activities. Is this new regime really helping with that?

When we look closely, the nexus approach has the potential to decrease the harmful tax effects of patent boxes on patent location and to raise the level of local innovation. However, there is the issue of the long waiting period before adopting the new regime, rendering the mitigation effects of the new nexus approach quite ineffective. People can still enroll into the old regime until June 2016 and benefit from it until 2021. If a number of businesses piled up into the old regime instead of waiting for the new regime entrance (also June 2016), the scope of the amendment will be affected. The end result will be a lessening of the only positive impact of the nexus approach.

Preferential treatments do attracts innovative activity, and Patent boxes are no exception. Only, the effect varies according to sectors. Bigger firms would be more inclined to use it, for example, or extensive patent companies (pharmaceuticals). This engenders a bias that is likely to create distortion in the British innovative system.

I do not contest the idea that the patent box is a strong idea. After all, the UK faced a growth crisis in 2013. The country was in dire need of an economy rebalancing towards productive entrepreneurship and the creation of new products and services. Only, this initiative, even after its amendment, doesn’t have enough empirical evidence that it serves another purpose aside from benefiting tax competition.

Still, some measures can still be taken to mitigate the role of patent box on tax competition. For instance, by changing the scheme so it does not include existent patents. Another option would be parallel investments to its knowledge economy. As the Work Foundation and the Big Innovation Centre argue, the “UK can not hope to maintain its living standards by competing in the world as a low-cost destination”. It should instead look for ways to develop the collaborative activity of its knowledge economy and make the British innovative system the real motor of value creation. That would certainly attract foreign investment. One would be motivated to come to the UK for the sake of achieving a particular goal, and not because it’s a ‘’cheap’’ tax destination.

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked with *