‘The refugee problem is a foreshadowing of the 21st century’s great migration.’

(“Nanmin mondai ha 21 seiku minzoku daiidô no zenchô da”, an interview by H.Uno, originally published on 17 August 1979, in Shûkan posuto, pp. 34-35. Translated from Japanese into French by Ryôji Nakamura, 1994 ; translated from French into English by Felix de Montety, 2015)

H. Uno: What according to you is the source of the problem of Vietnamese refugees?

M. Foucault: For more than a century, Vietnam has been continually occupied by military powers such as France, Japan and the United States. And now the former South Vietnam is occupied by the former North Vietnam. Of course this occupation of the South by the North is different from those which preceded it but it should not be forgotten that the power in place in South Vietnam is exercised from the North.

During this series of occupations over the course of a century, excessive conflicts have developed within the population. There have been a considerable number of collaborators, and you can put in this category merchants who traded with colonists, or regional civil servants who worked under the occupation. Because of those historical antagonisms, part of the population found themselves blamed and abandoned.

Many sense a contradiction between the previous need to support the unification of Vietnam and the current requirement to tackle the issue of refugees, which is a consequence of it.

The state must not exercise an unconditional right of life and death, over its own people or those of another country. To deny the state this right of life and death meant opposing the bombings of Vietnam by the United States and currently means helping refugees.

It seems like the problem of Cambodian refugees is not quite the same as that of Vietnamese refugees. What do you think?

What happened in Cambodia is absolutely unprecedented in modern history: the government massacred its people on a scale never before witnessed. And the remaining population that survived was saved, of course, but finds itself under the domination of an army which has used a destructive and violent power. The situation is therefore different from that of Vietnam.

On the other hand, it is important that, in solidarity movements which are organised throughout the world for refugees from South East Asia, the differences of historical and political situations are not taken into account. This does not mean that we could remain indifferent to historical and political analyses of the refugee issue, but in an emergency what should be done is to save people in danger.

Because, at the moment, 40,000 Vietnamese are drifting off the coast of Indochina or wash ashore on islands, on the brink of death. 40,000 Cambodians have been pushed back from Thailand, in mortal danger. There are no less than 80,000 people for whom death is a daily presence. No discussion on the general balance of power between countries of the world, and no argument about the political and economic difficulties that come with aid to refugees can justify states abandoning those human beings at the gates of death.

In 1938 and 1939, Jews fled Germany and Central Europe, but because nobody received them, many died. Forty years have passed since, and can we again send 100,000 people to their deaths?

To find a global solution to the problem, states that create refugees, notably Vietnam, should change their policy. But how, according to you, can this general solution be achieved?

In the case of Cambodia, the situation is much more tragic than in Vietnam, but there is hope of a solution in the near future. We could imagine that the formation of an acceptable government by the Cambodian people would lead to a solution. But as for Vietnam, the problem is more complex. Political power has already been established: but this power excludes part of the population, which does not want it anyway. The state has created a situation in which those people have to seek the uncertain chance of survival through an exodus by sea rather than by staying in Vietnam. Therefore it is clear that it is necessary to put pressure on Vietnam to change this situation. But what does ‘to put pressure’ mean?

In Geneva, at the UN conference on refugees, participating countries have exerted pressure on Vietnam, in the form of recommendations and advice. The Vietnamese government then made a few concessions. Rather than abandoning those who want to leave in uncertain conditions, and what’s more, at risk of their lives, the Vietnamese government proposes to build transit centres to collect potential migrants: they would stay there weeks, months or even years until they could find a host country. But this proposal sounds curiously like concentration camps.

The refugee issue has come up many times in the past, but if there is a new historical aspect in the case of Vietnam, what might that be?

In the twentieth century, genocides and ethnic persecutions happened frequently. I think that in the near future, these phenomena will happen again in new forms. First, because over the past few years, the number of dictatorial states has increased rather than diminished. Since political expression is impossible in their country and because they do not have the force necessary to resist, people repressed by dictatorship will chose to escape from their hell.

Second, in former colonies, states were created retained colonial borders as they were, so that ethnicities, languages and religions were mixed. This phenomenon creates serious tensions. In those countries, antagonisms within the population are likely to explode and bring about massive displacement and the collapse of state apparatuses.

Third, developed economic powers that needed labour from the Third World and developing countries have imported migrants from Portugal, Algeria or Africa. But, now, countries which no longer need this workforce because of technological evolution are attempting to send those migrants back. All these problems lead to that of population migration, involving hundreds of thousands and millions of people. And population migrations necessarily become painful and tragic and are inevitably accompanied by deaths and murders. I am afraid that what is happening in Vietnam is not only an after-effect of the past, but also a foreshadowing of the future.

Originally published by Progressive Geographies.

1 comment

1 Comment

Heterotopias of Crisis and Deviation – culturalspacesblog

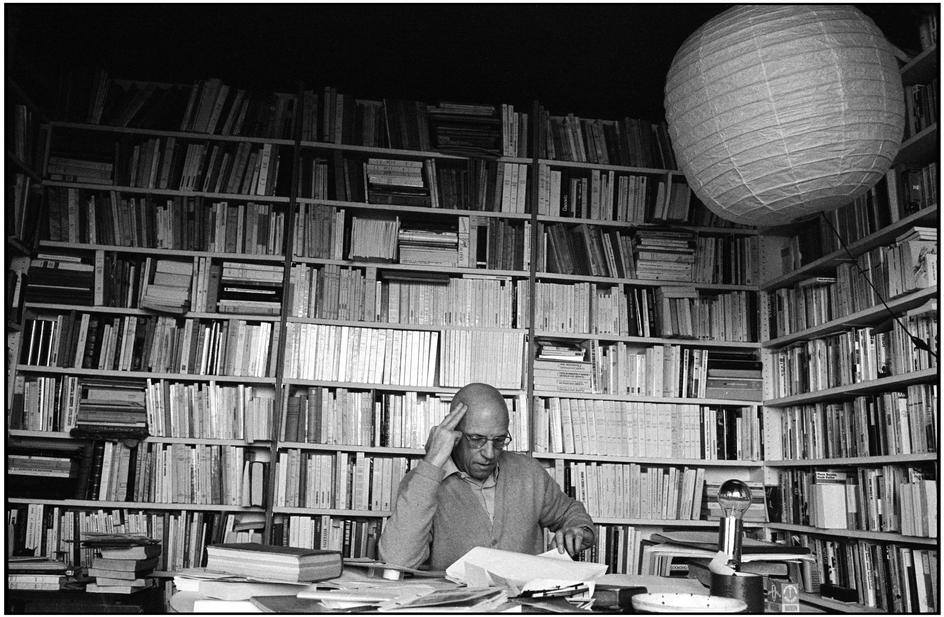

04/10/2016, 12:30 am[…] Fig. 1. Michael Foucault at study. Image source: http://politheor.net/michel-foucault-on-refugees-an-interview-from-1979/ […]

REPLY